We just returned from two days of field research. We found some important photographic stations of William Osgood Field, one of the first explorers of the 1900s who visited this area of the East Branch of Glacier Bay. We are so tired, there are no trails here and the dense vegetation continually hinders our progression and view. We define the ascent route each time by looking at the various mountainsides from below, moving by boat. Each time therefore we do not know what inconveniences and problems we will encounter. On the one hand it is frustrating because we never know if we will be able to reach the photo stations, on the other hand it is challenging because we have to find the most convenient ascent route ourselves, but in case of success, the satisfaction is definitely greater.

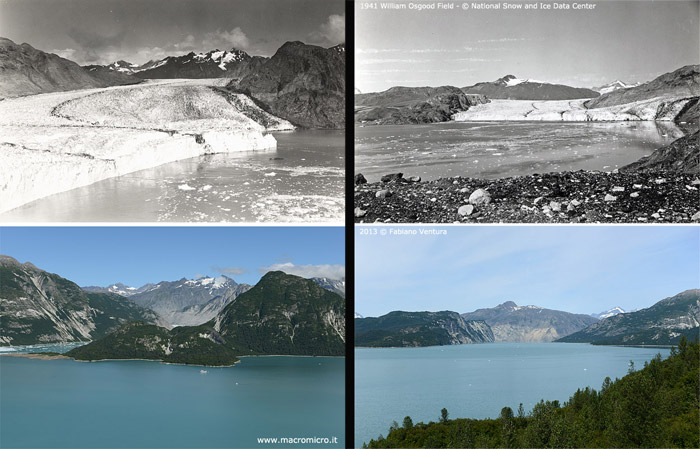

Tuesday morning we land with our speedboat on a beach near the bed of a small river, our plan being to ascend it in order to have a trail to follow on the valley floor. Unfortunately, as soon as we enter the forest we are immediately blocked by the now proverbial Alaskan jungle and forced to jump between alder branches two to three meters above the ground. Arriving at last on a small rise, I climbed a fir tree to get a better view of the rock face that without much difficulty would take us to the top of the second rise of the White Tunder Ridge. From this position at 300 m elevation overlooking the fjord, in 1941 William O. Field placed the historic No. 4 photo station. At that time the foreheads of the Muir and McBride glaciers were joined and almost within reach while today the forehead of the latter is barely visible. After waiting for the same shooting time as in the past, I repeat 5 images by Field and a nearly 360° panorama by Richard U. Light from 1952. Immediately, given the bird’s-eye view, I realize the great changes in the landscape and how much climatic conditions may have changed in just 72 years. In fact, from the comparisons we post below in the gallery you can see how ice at the time covered much of the valleys and entire hillsides, not to mention the dense vegetation that had grown up throughout the area.

In the afternoon, after reaching our speedboat, we look for a stretch of coastline where we can set up our base camp and set up our tents at a spot that we thought was out of the tide line. To make sure of this we look at a photograph of this beach taken in the afternoon from above at a time when the high tide was at its highest and realize that our tents are not safe at all, so we decide to move them to a clearing higher up. As scripted the water in the night rises and even laps at our new elevated spot, it would have been absolutely no fun to wake up at night with our feet soaking in the icy water.The next day we head for Nunatak, a rock outcrop that emerged isolated from Muir Glacier until the early 1900s and then became an actual mountain. The north ridge turns out to be too steep, full of bushes and rock jumps; at the base of the south ridge, however, there are two huge gresly bears hunting salmon. We therefore decide to postpone the ascent and set out in search of photo station No. 2, which appears to us to be more accessible.

As always, the bushes limit our progression and view of the mountains so much, which is necessary to find the correct alignment to repeat the historic photo. After a good three hours of up and down in the dense forest, I am forced to climb back up a large tree to repeat the historical shot. The picture succeeds very well, however, all the mountains turn out to be in the same position as the historical one, and satisfied we head back to the coast to return to Gustavus.